|

|

|

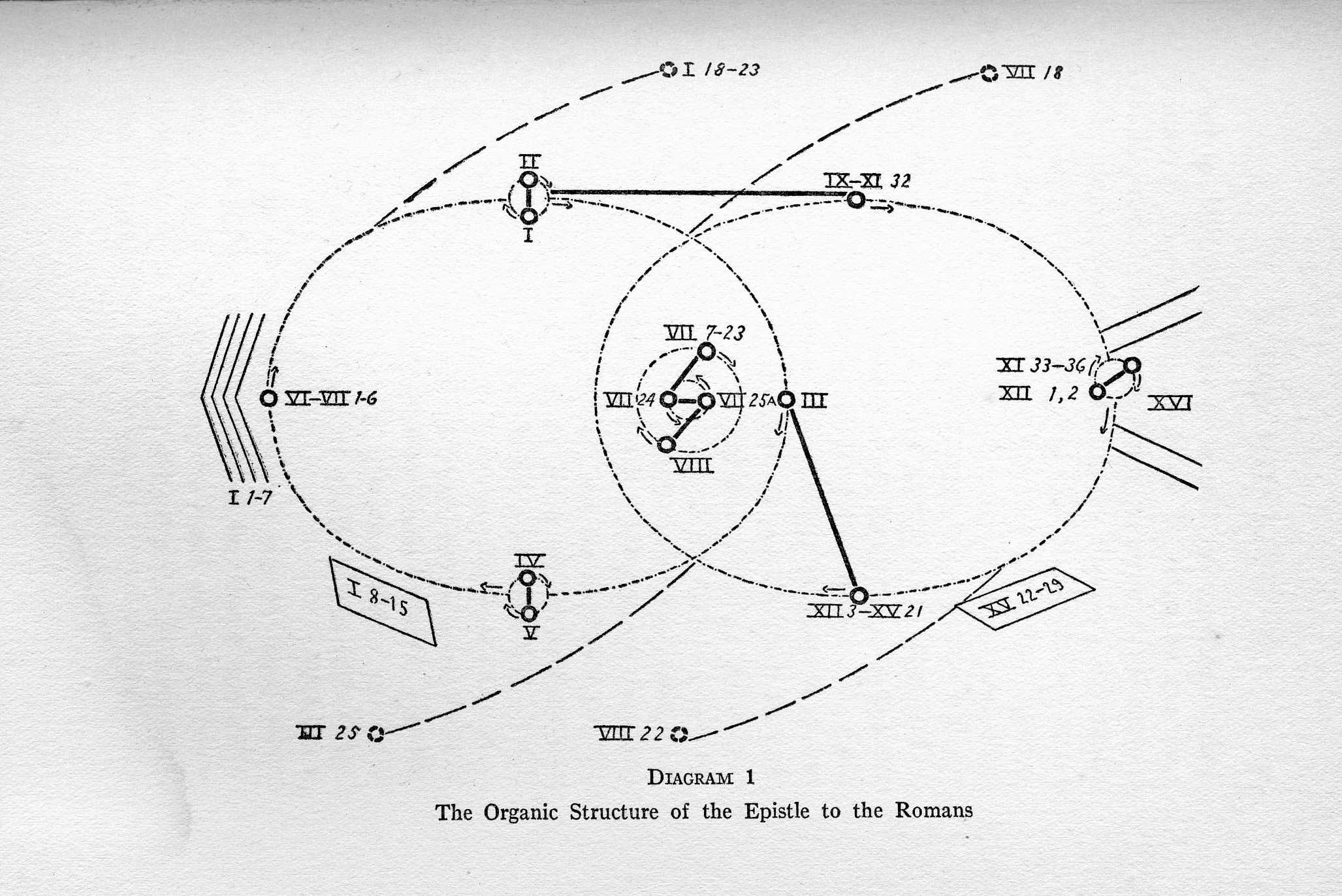

Now for our electrons, the chapters which are built upon, and which relate directly back to, our proton, chapters seven and eight. I have already said that the first six chapters are directed particularly to our intellectual faculty. So here they are on the orbit at the left. Chapters one and two are so closely related that I have put them in as a twin electron or planet. They are simply a universlization of what Paul discovered first in himself, his will-lessness, his mechanicality. In chapter one he says that like himself the Gentiles have not righteousness, that is, they cannot control their actions, they are "in the flesh." In chapter two he makes the same statement as to the Jews.

With chapter three Paul directs attention to the second half of the double statement which constitutes our proton, that is, Who shall deliver from sin? In chapter three he says that faith in Christ is the answer. In chapters four and five, which I have made a twin planet because of their relation to each other, he undertakes to demonstrate by illustrations from the Old Testament, the thesis of chapter three that faith is the way out of sin. We have observed how he and his hearers were conditioned by their upbringing1 upon the Old Testament. In chapter four he refers to the history of Abraham, and in chapter five to the history of Adam.

Now do not think that Paul in chapters four and five tried to prove from Abraham or from Adam the fact of sin or of faith. He simply used apt illustrations. Particularly the chapter on Adam has been objected to, where he says, "As in Adam all died, so in Christ all are made alive" etc.; the inference being that all his theology is based on what is at the present time considered to be a myth, and that the ridiculiousness (if we may say it) that we are all sinners because Adam sinned, leads to the thought of an equal illogicality, that if Christ was made alive we are saved by him. But you must remember that Paul, undoubtedly accepting the story of Adam, did not think that it proved anything to him; it was simply an illustration that appealed to his hearers as well as to himself. The proof of the pudding for Paul was this: He said, "I see in myself the war of the members." That was the point with Paul.

Further in regard to his use of the story of Adam. The other day I was reading over some of the Platonic dialogues, and I was quite struck with a passage in the Paedrus where Socrates had alluded to a Greek myth, and one of his followers said, "Why, you don't believe in a myth like that one, do you?" They were almost as modern in that time as we are. Socrates said, "Of course I accept the myths. I wouldn't take the trouble to disbelieve them. I have no leisure to investigate their truth at all: and the reason, my friend, is this: I am not yet able, as a Delphic inscription has it, to Know Myself. So it seems to me ridiculous when I do not know this, to investigate irrelevant things. Therefore, I dismiss these matters and accept the customary belief about them. As I was saying just now, I investigate not these things, but myself, to know whether I am a monster more complicated and more furious than2 Typhon, or a gentler and simpler creature to whom a divine and quiet light is given by nature."

That is the situation: whether it is better, as with Paul, to see himself, or to be able critically to distinguish between the historical and non-historical in the stories.

Reverting to the diagram, we have still to deal with chapter six, the last electron in the first orbit—the intellectual orbit. In that chapter Paul is approaching closer and closer to the heart of his doctrine. There he develops what faith is. He has said that what saves is faith in Christ; here he explains what faith in Christ is. It is not any form of belief or loyalty, but it is nothing less than dying with Christ, a process of voluntary suffering which must develop in us the action and attitude which Christ took. You may accept that or you may not; but that is undoubtedly Paul's message.

We have now finished the first orbit of electrons. The Epistle to the Romans is a long letter, and you may think that there are a great many words about two little phrases, for the whole letter is nothing but, "Oh, miserable man that I am, who shall deliver me? God!" That seems too small a nucleus for such an organism. But let us consider. If we go back to our Eddington, we find that such are the spaces—empty spaces we call them—in an atom that if the substance of a man were actually compressed so that there was left no intervening space, but only the substance of the protons and electrons, he would be so reduced that he could hardly be seen with a magnifying glass. Paul has been a little more considerate of us. We do not have to use a magnifying glass. We have only to open our eyes; not necessarily, though, only our optic organs.

1 PtS-32 has 'bringing'.

2 PtS-32 has 'that'.