I venture to use another similitude drawn from organic life. We refer to the peeling of an onion. The outer and less fundamental lines of thought in the epistle are represented by the outside layers. Then as we take off each layer, we get closer to the heart of Paul's thought, and finally reach that vital centre. Only we must remember that Paul did not work from the outside in as we do. He worked from the centre outward or better still, he saw the thing as a whole.

You must appreciate that the reason for this is that Paul is not thinking at all, as we use the word "thinking." His process of mentation is quite independent of any of the canons of rhetoric or literature. He is living, and is simply trying to picture his living. When any of us think we necessarily think by association. One thought follows the other. Our minds are so constructed that we cannot think in any other way. That is why ordinary writing has logical succession, and that is why we are disappointed when we do not find it in St. Paul. But when we come really to live, it is different. At those high moments we do not stop to think, we see the whole subject at once. We do not follow out the paths of a maze and reach our conclusion by association, but we look down on the whole subject and see all the paths at once, and we go directly to what we are after.

For instance, to use a very homely and, perhaps, silly illustration, if you see your mother attached by a dog, you do not reach the conclusion what to do by any logical sequence of thought; you do not think of the comparative value or worth of the dog and of your mother in the universe; you do not think of the possible danger to you; you do not think whether or not she might be able to defend herself without your aid, or perhaps better than if you interfered, but you jump right into the situation. All these considerations are, not in your mind, but in your being, at once.

And that was the way with St. Paul. He was not theologizing. He was not reasoning about proofs of God. He was not thinking out proofs of the existence of sin, as he called it, but something wrong in us. He was not thinking of any logical demonstration of the cure. But he was vividly alive to the fact of sin in himself. He was vividly alive to the fact that there had been given to him a way out. That is the heart of his doctrine, and the whole letter is dependent on just that fact of experience. The various chapters are merely expansions and illustrations of this central thought. They relate back directly to that central thought but only incidentally to each other. So if we start not with the printed beginning of the letter, but with the central thought, we find that there is a beautiful, organic structure.

|

|

|

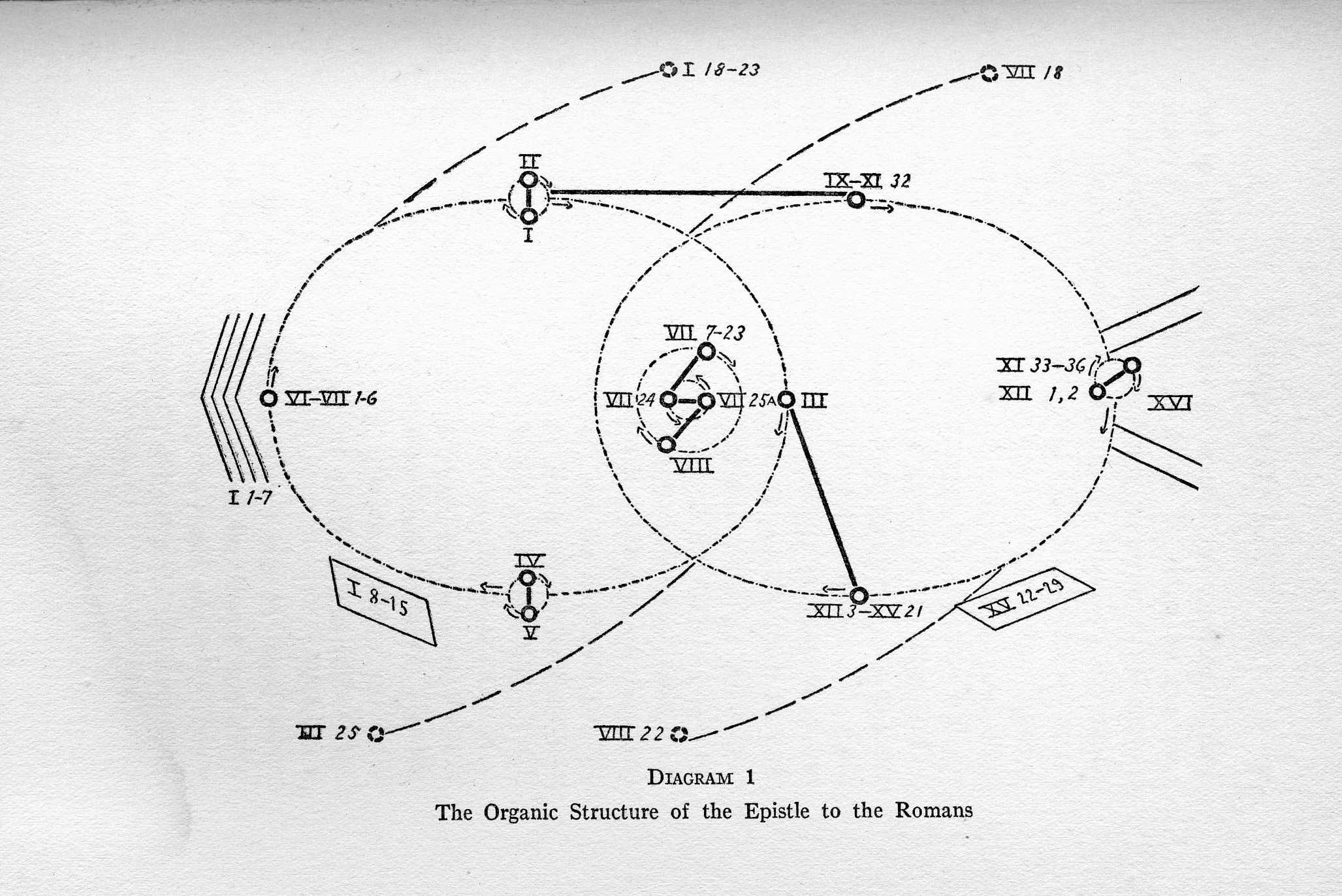

It is very hard to express this in words, and I do not know how it can be done adequately, for the subject matter is life not logic. But in making the attempt I want to use this diagram (diagram 1). Perhaps you will laugh at it, but at any rate, it will be a peg on which to hang my remarks. Somebody told me that it looks like an insect. I asked why, "Because those things look like antennae." I said, "Antennae don't grow out of the body, they grow out of the head." However, I am not entirely displeased if it looks something like an insect, because I feel that this epistle cannot be depicted only by somehing which is alive. Of couse I do not think that the diagram actually depicts the structure of the epistle, but I think at least that you will find it useful as an aid in following my words, just as I found it useful.