AMONGST the material received by John Linnell from William Blake and sold at the dispersal of the Linnell collection at Christie's in 1918, were five pencil drawings for the Book of Enoch. They appear as No. 129 of the uncoloured works in the annotated lists of Blake's paintings, drawings and engravings compiled by William Michael Rossetti for Gilchrist's Life of William Blake.

The drawings are on folio sheets, two of which are watermarked W. ELGAR 1796. The others are without dated watermark. Two of the sheets are endorsed at the top from the Book of Enoch, two are endorsed Book of Enoch, and one, B of Enoch.

Geoffrey Keynes in his bibliography while noting that these may have been illustratons to the pseudepigraphical Book of Enoch, lists the series under the head of Works Lost or Conjectural, and states that the indications on the designs suggest that the Book of Enoch may have been a projected work of Blake's. Keynes admits that such a work is not referred to elsewhere, but he is apparently influenced in his opinion by the notation on the side of one of the sheets, No 26 next at p.43. This notation, like the other endorsements, is not in Blake's handwriting. In any event, the fidelity of the designs to the text of the early work, in minute particulars which can not be accidental, shows that they are not illustrations of an original work by Blake.

The drawings are preliminary sketches instinct with all the spontaneity of primary artistic conceptions. While strikingly characteristic of Blake both in drawing and meaning, they are quite free from the mannerisms which sometimes mar the effect of Blake's work for those weaker brethren whose power of imagination is darkened by memory of nature, if we may use the phraseology of the Descriptive Catalogue. Aside from their beauty and vigor, however, the drawings have distinct historical interest as exhibiting the power, range and continuity of Blake's mental processes during the latter part of his life. They deserve closer scrutiny than they have yet received.

While the drawings are undated, there is little difficulty in determining the period to which they should be assigned. The Book of Enoch, although exercising an important influence upon the writings of the New Testament, early fell into disuse, and was lost to western Christianity until an Ethiopic manuscript was brought back from Abyssinia in 1773 by James Bruce, the Scottish explorer. It seems little likely that Blake could have had any knowledge of the contents of the book until the year 1821 when the first English translation was published.

The Enoch drawings therefore must have been produced between 1821, when Blake was in his sixty-fifth year, and 1827, when he died. Probably they belong to the end of the period, for until 1825 Blake was occupied with the engraving of his inventions to the Book of Job, that tremendous epic into which he was able to put so much of his own theology. Then came the series of Dante illustrations, which, with all their overwhelming power, failed to give Blake the same opportunity for the promulgation of his own gospel. It is at this time that we might expect to find him searching about for other possible vehicles for his spiritual teaching. In fact, the drawings for Genesis, a series somewhat similar in character to the Enoch drawings, are dated 1827.

From Blake's "Descriptive Catalogue" it appears that earlier in life he had been sufficiently interested in the first published translation of the Bhagavad Gita into English to embody the incident in an ideal design. Small wonder then that the translation of the Book of Enoch attracted the atterntion of the close Bible student. Enoch is cited by name and quoted in the epistle of Jude, and we know that Blake had studied that epistle, from his water-colour drawing of Satan and the Archangel Michael contending for the body of Moses, an incident recorded only in Jude.

The Book of Enoch is a curious collection of diverse materials, including even a section which attempts to deal scientifically with the laws of the heavenly bodies. The book opens with the story of the fall of the angels and their intercourse with the daughters of men and of Enoch's unsucessful intercession for them before God. Then vision follows vision. The bounds of Sheol are traversed by Enoch and his angel guide. Famous sinners are seen in torment. God, the Lord of Spirits, and His Elect, the Son of Man, are seen and described in words of considerable beauty and poetic feeling. There is a vision of the last judgment. Finally the history of the Jews is narrated in symbolic form. The likeness of parts pf this work to the Dante epic in which Blake was so engrossed is obvious and has been heretofore pointed out. BLake's own Marriage of Heaven and Hell affords perhaps an even closer analogy. The whole book was eminently fitted to attract Blake's pencil as soon as its translation made it available to him.

Rossetti says that the Enoch drawing are "as intangible for description as the average of the designs of the Prophetic Books. A miscellany of naked figures in conditions that one does not accurately comprehend." We must conclude that Rossetti was not familiar with the Book of Enoch, for the drawings are in fact not at all obscure. The designs for Blake's Prophetic Books are not infrequently obscure because they do not follow the text but amplify and interpret it, sometimes even presenting new ideas only indirectly connected with the theme of the prophecy. The Enoch drawings on the other hand are like the Dante set in their careful adherence to the text which that illustrate.

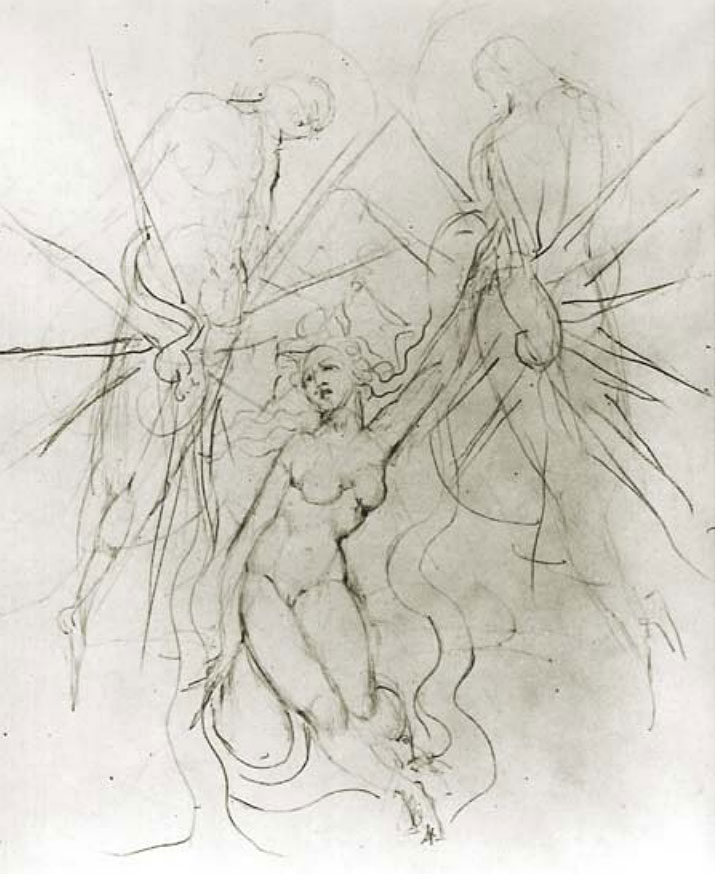

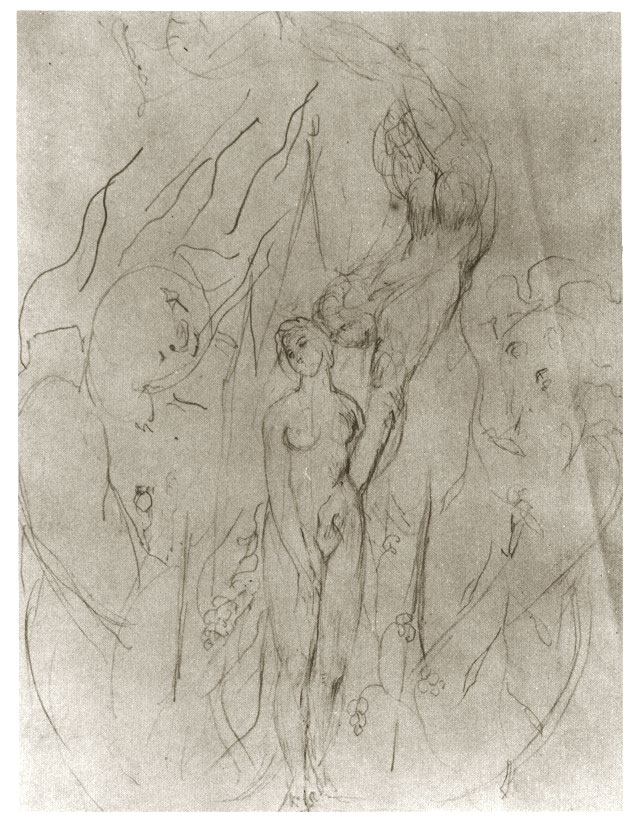

The first three designs illustrate the episode of the fall of the angels and represent three stages in that story of progressive degeneration.

And it came to pass in the days when the children of men had multiplied that there were born unto them beautiful and comely daughters. And the angels, the children of heaven, saw and lusted after them, and said to one another, "Come, let us choose wives for ourselves from among the daughters of man and beget us children." And they were in all two hundred; who descended and took unto themselves wives, and each chose for himself one; and they began to go in unto them and to defile themselves with them, and they taught them charms and enchantments and the cutting of roots, and made them acquainted with plants, and revealed to them all kinds of sin.

And they became pregnant and bare great giants, whose height was three thousand ells. And these consumed all the acquisitions of men. And when men could no longer sustain them, the giants turned against them and devoured mankind. And they began to sin against birds and beasts and reptiles and fish, and to devour one another's flesh and drink the blood.

And there arose much godlessness, and they commited fornicaton and were led astray and became corrupt in all their ways. And the whole earth was filled with blood and unrighteousness. And the women also of the angels who went astray became sirens.

In the first drawing the composition centers about the nude figure of one of the "beautiful and comely" daughters of men. Two angels descend towards her. By a bold and strikingly effective arrangement the angels are portrayed not only anthropomorphically but also in the guise of stars with phallic attributes. This is to accord with the symbolism of a later vision of Enoch where, with somewhat disconcerting bluntness, they are so represented. It is not to be believed that Blake conceived this notion independently. He could only have taken it from the Book of Enoch.

In the second picture the woman again occupies the center of the composition. An angel, descending with the rushing sweep which Blake could depict so masterfully, whispers in her ear the secrets of sin, particularly root-cutting and enchantments with herbs and plants, if we may judge by the surrounding leaves and flowers and branches. In the background at either side of the woman, and very striking features of the composition, are two of the giant children. They are not the only fruit of sin, however, for the attitude of the woman has clearly become acquiescent, while the body of the angel has begun to develop that scaly covering with which Blake so often invests the evil genius.

In the third drawing the moral debacle is complete. The woman has become a siren, or as we should perhaps say, vampire. Wearing the scales of sin, she rises exultant from the prone body of a man, while an innocent sister, balancing the composition, stands at his feet, frozen with grief and horror.

The fourth design portrays Enoch standing with his angel guide before the throne of the Great Glory, where he has come to plead for forgiveness for the fallen angels.

And I looked and saw a lofty throne: its appearance was as crystal, and the wheels thereof as the shining sun. From underneath the throne came streams of flaming fire so that I could not look thereon. And the Great Glory sat thereon, and His raiment shone more brightly than the sun and was whiter than any snow. None of the angels could enter and behold His face by reason of the magnificence and glory, and no flesh could behold Him. The flaming fire was round about Him, and a great fire stood before Him, and none could draw nigh Him: ten thousand time ten thousand stood before Him, yet needed he no counsellor. And the most holy ones who were nigh to Him did not leave by night nor depart from Him. And until then I had been prostrate on my face, trembling: and the Lord called me with His own mouth and said to me: "Come hither, Enoch, and hear My word." And one of the holy ones came to me and made me rise and appr[o]ach the door: and I bowed my head downwards.

The fifth design portrays the Messiah, called in Enoch the Son of Man, the Elect. He is shown surrounded by his four attendant spirits, counterparts of the four archangels of the presence of God. This drawing might well serve as a frontispiece for the entire work, for the Messiah doctrine is the most prominent and important feature of the book and Blake has grasped its full significance. The mingled majesty and tenderness of the figure make it by far the most successful of Blake's attempts at the portrayal of the Christ.

And I asked the angel who went with me and who showed me all the hidden things, concerning that Son of Man, who he was and whence he was and why he went with the Head of Days. And he answered and said unto Me:

This is the Son of Man who hath righteousness, with whom dwelleth righteousness, who revealeth all the treasures of that which is hidden; because the Lord of Spirits hath chosen him, and whose lot hath preeminence before the Lord of Spirits forever.

For he is mighty in all the secrets of righteousness, and unrighteousness shall disappear as a shadow and have no continuance. Because the Elect One standeth before the Lord of Spirits, and his glory is forever and ever, and his might unto all generations. And in him dwells the spirit of wisdom, and the spirit which gives insight, and the spirit of understanding and might, and the spirit of those who have fallen asleep in righteousness. And he shall judge the secret things, and none shall be able to utter a lying word before him; for he is the Elect One before the Lord of Spirits according to His good pleasure.

We have seen how closely Blake adhered in these illustratons to the text of the Book of Enoch. But the man of fourfold vision was not satisfied with this. Just as he was able in the first design to depict both the literal and symbolic aspects of the descent of the angels, so also he made all the designs a vehicle for the expression of his own doctrines.

In the first three designs is represented the evil domination of the Female Will, personified in his system as Vala. By this he meant material beauty, carnal love, leading to the sleep of materialism, spiritual death. This evil influence he described in the Prophecy of Europe, where Enitharmon, the Emanation of Los, is able, by appeal to the physical attractions, to sleep (that is, maintain the ascendancy of materialism) for 1800 years even after the birth of Christ or Orc. The doctrine is further expressed in Jerusalem, page 34, lines 25–35:

What may Man be? who can tell! but what may Woman be?

To have power over Man from Cradle to corruptible Grave.

There is a Throne in every Man, it is the Throne of God.

This[,] Woman has claim'd as her own, and Man is no more:

Albion is the Tabernacle of Vala and her Temple

And not the Tabernacle and Temple of the Most High.

O Albion, why wilt thou Create a Female Will

To hide the most evident God in a secret1 covert, even

In the shadows of a Woman and a secluded Holy Place,

That we may pry after him as after a stolen treasure,

Hidden among the Dead and murèd up from the paths of life?

In these designs the woman represents Vala. The mingled desire and distress upon her face in the first design exactly express Vala's lament in Jerusalem, page 33, lines 45–48:

Wherefor did I loving create love, which never yet

Immingled God and Man, when thou and I hid the Divine Vision

In clouds of secret gloom which, behold, involve me round about!

Know me now, Albion: look upon me: I alone am beauty.

It is significant that the posture of the woman in this design is a combination of the attitudes of the two central figures in design 99 of the Dante series. That design, which must have been produced at about the same time, represents the Queen of Heaven Enthroned. The Virgin Mary is pictured naked holding a mirror and a fleur de lis on a staff like a sceptre or thyrsus. The Virgin with Blake again and again represents the evil Female Will, the source of the carnal part of Christ.

In the second design the leaves and branches represent the vegetable life, which is Blake's term for the life of the senses. The giant children, their hair flames of passion, suggest the Book of Los, lines 25–26:

And Wantoness of his own true love

Begot a giant race.

In the third design Vala, triumphant, is covered with scales. She is thus represented in Vala, Night II: "she grew a scaled serpent," "Till she became a dragon, winged, bright, poisonous." The tree with Blake represents error. Descruction is now complete. Man sleeps the sleep of spiritual death at the foot of the tree. In the same way Eve sleeps at the foot of the cross in the Paradise Lost series. The second woman in this design represents Jerusalem, the Emanation of Albion, the tender part of his nature from which men by the fall became separated.

Jehovah, the God of punishment, was always abhorrent to Blake. This was Satan. His god was Jesus, the God of forgiveness. Therefor the features of the Almighty in the fourth design have something sinister. Blake could have pleaded the cause of the fallen angels better than Enoch did.

In the last design the four spirits represent the fourfold nature of man — humanity, spectre, emanation and shadow. This is the basis of Blake's doctrine of man. The design perfectly illustrates Vala, Night I, lines 4–6.

Four Mighty Ones are in every Man: a perfect Unity

Can not exist but from the Universal Brotherhood of Eden,

The Universal Man, to Whom be glory evermore. Amen.

New Rochelle, N.Y., 1925.